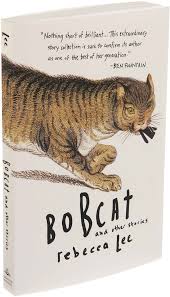

I recently had the pleasure of reviewing Rebecca Lee’s wonderful story collection Bobcat and Other Stories for the Chattahoochee Review (33.2-3).

OF DUST AND EROS: A REVIEW OF REBECCA LEE’S BOBCAT AND OTHER STORIES

Bobcat and Other Stories. Rebecca Lee. Algonquin. 2013. 212 pp. $14.95 (paperback).

Bobcat and Other Stories. Rebecca Lee. Algonquin. 2013. 212 pp. $14.95 (paperback).

One of my favorite poems is George Herbert’s “The Pulley,” in which he speaks of the “glass of blessings” God bestowed upon man at his creation. God imparts strength, beauty, wisdom, honor, and pleasure, but withholds “rest,” believing that if he gives him everything, man would “adore my gifts instead of me.” As Herbert writes,

Let him be rich and weary, that at least,

If goodness lead him not, yet weariness

May toss him to my breast.

The characters that populate Rebecca Lee’s Bobcat and Other Stories experience the same restlessness of Herbert’s poem. Lee’s characters are all propelled by desire: for love, connection, recognition, understanding, and a place in the world. Their desire as perpetual restlessness drives Lee’s stories and their characters, most of them academics, artists, and students.

The book opens with “Bobcat,” a big story in a small setting, and perhaps my favorite, about a dinner party between friends and narrated by a pregnant lawyer questioning the authenticity of her friends’ troubled relationships, as well as her own. I had just read the title story when I visited a friend one night while his wife and daughter were away. Over dinner we caught up on the routines of our lives. My friend spoke about a recent outing with his family he described as “nearly perfect” if not for an ongoing disagreement with his wife that left him frustrated and weary. He believed they would never settle the issue, and the constant friction troubled him. It was then that I fully understood Lee’s story, particularly the sentence in which the protagonist’s husband is seen squatting in an Irish field: “This field grew out of not dirt, but pebbles really. It surprised me that anything could grow out of those stones, but there was a bright-green grass that seemed to be thriving, and a lot of bluebells” (16).

Lee guides us through the cozy but extravagant dinner party with friends and colleagues, in which the French dessert, a terrine the protagonist attempts, the “perfect melding of disparate entities,” reflects how relationships survive and fail in similar states (3). Such an assembly of ingredients, such care and effort to create a dessert barely contained in its own wobbling shell. The volatile mix of components feels like the marriages we witness in the story—a chaotic splendor, each one on the verge of collapse. It’s what they, and, by association, we do with this potential for collapse that keeps us invested and going forward. When a friend of the protagonist declares she wants none of it and asks why people fall in love and get married, the narrator rationalizes that “nobody really knows. But that doesn’t mean you’re allowed not to do it” (12). It’s in the doing, in the attempt at order, that we find the answer. Lee reminds us, “You would no more expect to find peace within a family than you would expect to find it in yourself” (16). We are all chaos barely contained. Though the protagonist’s marriage will not survive infidelity and a miscarriage, she recognizes, like her client, a Hmong immigrant on trial for allowing his wife to die when he refused to seek Western medical treatment, that sometimes God requires “a living sacrifice in place of a person, to balance out the forces of life and death” (19).

I found familiar territory in the other stories too, as Lee evokes nostalgia for an academia cradled in perpetual autumn, when professors were wrapped in “elaborate historical” (65) selves, comfortable and imposing in offices overlooking campus color, when “murderous innocence” (63) and youthful desire were offered in exchange for knowledge and distinction. Her nostalgia is steeped in an appreciation for art and language, its limitations and possibilities, musical descriptions affectionately rendering scenes on college campuses, across elegant dinner tables with colleagues, and at rural artistic residencies. There were so many lovely passages that my copy of the book is dyed in yellow highlighter. This review could easily have been a collection of those lyric moments. Lee’s characters allude to Ovid, Rilke, Auden, and Wharton. Readers outside academia or the arts might find the nostalgia isolating. But academia merely gives Lee’s characters a setting in which to struggle with the universal desire for permanence and order. Lee finds particular wealth when she mines the relationships between student and teacher, as told from the student’s point of view, reflective, often whimsical, first person recollections that probe the mysteries of relationships, art, and language.

In “The Banks of the Vistula” we witness a relationship borne of deceit when a freshman plagiarizes her first linguistics paper in order to stand out. Her professor recognizes the plagiarism, stolen from a rare text of Soviet propaganda, and they embark on a game of cat and mouse in which the young woman’s professor befriends and eventually coaxes her to own the text she has stolen at a university symposium, despite its outdated and shocking content. The student Margaret says:

He was my teacher… and [he] stood in front of the high windows, to teach me my little lesson, which turned out to be not about Poland or fascism or war, borderlines or passion or loyalty, but just about the sentence: the importance of, the sweetness of. And I did long for it, to say one true sentence of my own, to leap into the subject, that sturdy vessel traveling upstream through the axonal predicate into what is possible; into the object, which is all possibility; into what little we know of the future, of eternity—the light of which, incidentally, was streaming in on us just then through the high windows. (65-66)

The beautiful “Fialta” explores a similar student/teacher dynamic when an architecture student discovers the incongruities between desire and fulfillment at an artistic residency (Fialta) hosted by the fabled mentor Franklin Stadbakken, whose single restriction is that residents not sleep with each other. The protagonist finds his longing for Sands, another resident, is complicated by Stadbakken’s own problematic interest in the student. He asks Sands if Stadbakken is in love with her. “‘Not in love, no,’ she said. Which of course made me think that his feelings for her were nothing so simple or banal as love” (169). Like many of the other stories in this collection, underneath the narrative tension we find that life is like “the simplest buildings,” which ought to be “productions of the imagination that attempt to describe and define life on earth… an overwhelming mix of stability and desire, fulfillment and longing, time and eternity” (178).

In “Min,” Sarah, a restless American college student in the late 1980s, accepts an invitation from her classmate to spend a summer in Hong Kong working for his father at an overcrowded and politically sensitive refugee camp. She also agrees to interview prospective brides for Min’s arranged marriage, using the notes his grandmother took when fulfilling the same duty for Min’s father years before. While Sarah wrestles with her own desire, for both Min and a clearer understanding of a world out of balance and suffering “compassion fatigue,” she discovers that longing does not always lead to fulfillment (102). In the grandmother’s notes, she finds a formula for women: “two-thirds contentment, one-third desire,” a principle that “seemed to capture the entire world in its tiny palm” (117). Summer ends and Sarah concludes her interviews, introducing Min instead to an unlikely prospect she meets in a street market: an outspoken Filipino amah whose background would be “a lot to overcome” (125). As Sarah witnesses Vietnamese refugees preparing to be deported, she realizes that desire can sometimes become a liability, an ache that will never be satisfied.

Lee unearths beauty in every landscape whether in a post-dinner party bliss and the fantasy of timelessness that resides there to the “collection of mangled bones” that “every man stands before as he declares life good.” Like the husband in the title story, Lee believes words are “fascinating—their origins and mutations, their ability to combine intricately,” and shades each story as a “collection of treasures, a pleasure-taking, a finding of everything praiseworthy.” Her characters long for fulfillment professionally and personally, but find that human relationships are thorny and happiness is elusive. In this transformation of desire into art Lee finds life in the “little treats—little chocolates and liqueurs, after the meal, so that as the night decelerates there is no despair” (28).